Coaching Corner

Welcome to Coaching Corner

The pieces shared below are adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. Each segment is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, I encourage you to explore the book in its entirety.

Contents

Active questions

Asking and listening

Assessing your focus

Building awareness of traits

Changing a beliefs

CIA model

GTD's Natural Planning Model

Engaging in the moment

Identifying limiting labels

Instant Sleep

Kofman’s approach

Lion in chains

Managing derailing behaviours

Managing emotions

Managing the ego

Mastery in accountability

Mastery in crafting

Retrospectives

Scaling Questions

Searching for limiting behaviours

Social Needs Relationship Matrix

Strengthening the attention muscle

Surfacing core values

Taking stock

Testing your perspective

The Amygdala Hijack

The Theatre Metaphor

Three-week gratefulness challenge

Understanding beliefs

Active questions

Maintaining momentum is important if you have any hope of making the necessary adjustments at the right frequency to avoid the challenge proposed with respect to the rocking chair. The rocking chair concept illustrates the ideal of reflecting on life with no regrets, acknowledging that true awareness and effective decision-making are challenging due to the limitations of memory and the complexity of life's variables.

A well tried and tested method for maintaining momentum is the daily use of active questions as proposed by Marshall Goldsmith and Mark Reiter, in their 2015 book, Triggers, Creating Behavior that Lasts, Becoming the Person You Want to Be. This involves establishing Active Questions in your daily routine.

These self-reflective-based questions start with, ‘Did I do my best to’ and end in something that you are working towards. Examples would include, ‘to be a committed team member’, ‘to be a caring friend’, ‘to be a loving spouse, and ‘to be an engaging parent’.

The process to experience active questions is as follows:

- Take a piece of paper and write down the aims or behaviours you are hoping to adopt or adjust (i.e., exercise regularly).

- Now, think of how you would measure your progress by considering what question could assess if you are doing what you committed to (i.e., ‘Did I go to the gym?’). Write those ‘measurement’ questions on a separate page. Repeat this for each of the items on your aims and behaviours list.

- Next, for each of the ‘measurement’ questions, ask yourself how you performed in the context of yesterday (i.e., ‘Did I go to the gym?’). If this is a new behaviour, ask as if you have already started. Give yourself a score between zero (0) and ten (10), where zero is farthest from where you want to be and ten is closest. Write the scores next to the measures. As you ask the questions, observe what you start thinking about. When done, turn over the page or hide the ‘measurement’ questions and their scores.

- Now, on a further piece of paper, write a new set of ‘measurement’ questions, but this time start them with ‘Did I do my best to’ (i.e., ‘Did I do my best to go to the gym?’)

- Finally, for each new ‘measurement’ question in the ‘Did I do my best’ format, reflect on yesterday again. Once more, give yourself a score between zero (0) and ten (10), where zero is nowhere near your best and ten is your absolute best. Write the scores next to the measures. As you ask the questions, observe what you start thinking about.

After doing this exercise you will likely find that active questions are less critical of your performance. This is because you immediately have context of what was happening yesterday. And, more importantly, the active question has your mind looking for proactive ways to move forward. Often, we fall short of what we want to achieve because we fail to use measures that drive us forward instead of holding us back. Normal measures are too focused on what you knew at the time of defining the measure and don’t consider the context of where you have found yourself later. Changes in context include things that change in your surrounds that are beyond your control (i.e., weather, serious illness, death as well as changes in your home life, workplace, and communities).

The best practice is to construct a set of active questions and then score them on a regular basis, perhaps daily. Over time the questions change, as your context, and needs shift.

Below are some examples of active questions to use daily:

- Did I do my best to balance my intake of food with my use of energy?

- Did I do my best to grow and learn?

- Did I do my best to capture my aims and statements of gratitude?

- Did I do my best to be an authentic father?

- Did I do my best to experience companionship?

- Did I do my best to experience intimacy?

- Did I do my best to be an authentic son?

- Did I do my best to be an authentic brother?

- Did I do my best to be an authentic friend?

- Did I do my best to maintain the conditions for being my best - personally?

- Did I do my best to maintain the conditions for being my best - professionally?

- Did I do my best to create the conditions for Otherish Giving?

- Did I do my best to write?

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Asking and listening

The process of asking and listening, can be summarised as follows:

- At any moment, be it when things are going well or when they are not, ask yourself, ‘What actions will bring me closer to what I want and need?’.

- After asking, pay attention to the thoughts that show up. Use the responses you get from listening, to drive your actions.

During this process be sure to give yourself some room to explore and to be wrong. You can’t be expected to have all the answers and get everything right. Forgiveness is the key to learning. If you keep control of your thinking, you’ll get plenty of signposts along the way. From there you can correct your path.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Assessing your focus

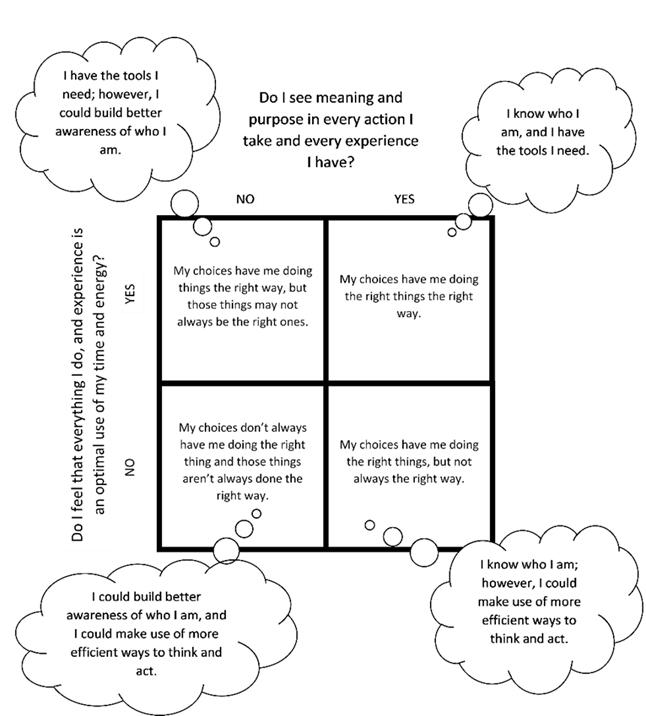

The following assessment is helpful in assessing where your focus is as you look at the choices you have before you.

The assessment has two questions.

The first question is to ask yourself if you see meaning and purpose in every action you take and every experience you have. In other words, are your experiences free of doubt or burden?

The second question is to ask yourself if you feel everything that you do and experience, is an optimal use of your time and energy. In other words, are you always in a calm state and getting what you want done in the time you want it to get done?

If you answered No to both questions, you are often finding yourself doing things that you don’t feel serve you. You are likely finding that getting things done is hard and exhausting.

If you answered yes to the first question and no to the second question, you feel good about the things that you are doing, but you are still exhausted and continually playing catch-up.

If you answered no to the first question and yes to the second question, you are doing things well and maintaining a good level of energy, but you don’t feel you are doing enough to get ahead or serve others well.

If you answered yes to both questions, you are in flow, maintaining energy, and doing wonderful things for yourself and all those around you.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Building awareness of traits

Personality traits, or just traits, are defined as enduring patterns of perceiving, relating to, and thinking. That all relates to both our environment and how we see ourselves. In other words, they, with core values, are the building blocks of our belief system.

Building awareness of traits can be done via psychometric tools like ‘The Big Five Aspects Scale’, which is found at understandmyself.com/personality-assessment

After taking a test like this, look at the examples provided in the text to see if it validates the results. Then extract out a list of positives and negatives from each of the big five personality traits (and within each of their two aspects). The positives are aspects you should leverage more, and the negatives are things to work on managing.

Note: Personality tests are self-reported and as such, they are relative to how you are feeling and what is going on around you when you take the test. Furthermore, while these tests do their best to catch attempts to mislead the results by asking the same question in several different ways, with practice and good knowledge of how the test works, the test taker can sway the results in the direction they want. This isn’t helpful for recruiters using the tests as part of employee placement. Nor is it useful if you want to really understand more about yourself. All of this has the potential to hold you back and reduce your agency.

Awareness can also be built by observing your behaviour. Like peeling layers of an onion, while straightforward, it does take effort, and time. Removing one layer of the onion allows you to get at the next layer. With each new understanding comes a new perspective.

To self-study your behaviours, you engage two parallel activities. The first activity is to spend time considering what you do well and where that is serving you. The steps for this are below. The other parallel activity is to observe your daily routines and practices and reflect on the skills you are deploying.

These questions help surface traits:

- What am I good at?

- What are my dominant gifts?

- What am I best at?

- What natural abilities do I have?

- What do I do that gets a positive response from people I respect?

- What do I do that does not seem like work, regardless of the difficulty?

- What do I do that causes doors to open with ease for me?

- What excites me?

- What activities do I enjoy the most at work, at home, or in social situations?

- What am I passionate about?

- What do I love spending time on?

- What desires keep tugging at my heart?

- What motivates me when I am most productive?

- What do I do that makes me feel good emotionally and spiritually?

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Changing a belief

Beliefs drive our behaviours, consciously, and unconsciously. We use beliefs to evaluate our experiences. Also, in a sense, beliefs encompass our goals in that, goals represent the desired future state of something that we value.

Beliefs address everything we do and experience. We have beliefs about what we eat, how we dress, and who we socialize with. Beliefs address the simplest of notions, like that of wearing matching socks. They also address more complex ideas of what we believe about how we greet people we have just met (i.e., should you shake hands firmly, go for one peck on the cheek or is it two, or even three, or what about a bear hug?)

The process of changing a belief is as follows:

- When you find yourself disappointed with something you are doing or you perceive others are doing to you, you ask yourself, ‘What do I believe to be important about this?’. Listen to the answers and then write these down.

- Then for each thing you have written down, ask yourself these questions: ‘What is important about this belief?’, ‘What does it give me?’, ‘Where does it put me?’, ‘Where is it used?’ Write these answers down too.

- For each of the subsequent answers, ask yourself ‘What is important about this?’, ‘What is the context of this? What am I assuming?’.

- Now, reflect on what occurs to you as you read what you have written.

If little comes of that reflection, check your memory for other times you have applied the same sort of logic and look for anything else related to assumptions and context. After this process, one of two things typically happens next. Either you find that you have borrowed this belief, or you no longer value the reasons on which the belief was based. In all cases you should either find a better way or find that you are now willing to search for one. Once you have clarified the reasons behind what you believe, it should be easier to move on.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

CIA model

In the coaching world there is a model called ‘CIA’. This model is presented by Neil Thompson and Sue Thompson in their 2008 book, The Critically Reflective Practitioner.

The model is useful for breaking down complicated needs and wants. It has three elements, ‘Control’, ‘Influence’, and ‘Accept’. The control element represents aspects of your situation that you can control (i.e., your thoughts, feelings, personal stuff, and physical actions). The influence element represents the aspects in your world that you can’t control, but that you can bring some level of direction to, through your influence (i.e., where you have trust or authority). The accept element is for everything else (i.e., where you have no direct control or influence). The model is useful when you need to rationalize why you have resistance to a situation or choice. However, it misses the mark. you are never really in total control of everything. Nor are you truly able to guarantee the outcome through directing the actions of others. Life is just too complex.

Furthermore, even if you are doing something that is brave, failure to acknowledge the resistance puts you at risk. When you do not sense and acknowledge the resistance, you are in denial of it. An effective way to look at resistance is by looking at fear. While resistance is created from all our negative emotions, like disgust, boredom, hate, envy, sorrow, anger, frustration, discontentment, alarm, guilt, indifference, it is fear where we can see it clearly. To understand light, you must have dark. To understand agency, you must have resistance. To understand the resistance, you can explore the fear that holds you back: the fear of putting your views forward; the fear of asking for what you need; the fear of going after something you want; the fear of saying no, or the fear of letting go of something you have. Resistance isn’t really about effort or work. There will always be things you don’t feel like doing but must do, like cleaning the house, medical check-ups, or sharing sad news. At the core of the resistance is a conflict in your mind and heart as to the alignment of the experience to what you feel is right for yourself and for those you care about.

Breaking down your choices by ‘Control’, ‘Influence’, or ‘Accept’ sets you up for disappointment. This is because the ‘accept’ is always the fall back. Unfortunately, accepting something that isn’t aligned to what you feel is right eventually grinds you down and that can turn to frustration and anger.

A better approach is to look at things slightly differently when you are trying to rationalize why you have resistance to a situation or choice. This still involves the use of the CIA acronym and the premise, but with different meaning given to the letters. ‘C’ is for ‘Create my reality’ and relates to actions you can take. These are the actions that will help you create the reality that you want, the person you want to be, and to create your physical, mental, and connected best self. Focus here brings direct benefit and experiences for yourself and those you care about. The ‘I’ is for ‘Integrate my reality’ and is one step back from actions that fit directly with your path. Integrating is about combining your and others’ actions into a single shared reality (i.e., where there is a shared goal or direction, in partnership, team, or group situations). The final aspect is the ‘A’ and stands for ‘Aligning my reality’. This is where you use the actions and experiences of others definition in bringing you closer to the reality you want and desire. It’s about choosing to use the path set out by others to learn and grow. Examples would be joining a Camino Walk where someone else sets the path and pace, or playing a game with enthusiasm and vigour, using the odd rules defined by your child, or embracing the potential of an arranged marriage. Actions that integrate you with someone else’s path and purpose, do help you. It is a form of Otherish Giving, as explored by Adam Grant in his 2014 book Give and Take: Why Helping Others Drives Our Success. This kind of giving brings benefit to others, without compromise to your own experience or wellbeing. In this way, engagement and alignment with your journey and ultimately your purpose, can be achieved in everything that you do and experience, no matter how much, or how little control or influence you have.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

GTD's Natural Planning Model

This short piece provides a summary of the David Allen's Natural Planning Model as outlined in his book Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-free Productivity. At the end is a template for use with your projects.

Click here to see a recording, where David talks about the model.This model helps you clearly define your projects, ensuring your focus remains on what truly matters, rather than being swayed by the latest trends or distractions. By comprehensively outlining both your ongoing projects and those you've decided to forego, you maintain a clear, strategic direction in your work.

Natural Planning Model

1. Purpose/Guiding Principles (Why?)

The purpose and principles are the guiding criteria for making decisions on the project.

- Why is this being done? What would “on purpose” really mean?

- What are the key standards to hold in making decisions and acting on this project? What rules do we play by?

2. Mission/Vision/Goal/Successful Outcome (What?)

- What would it be like if it were totally successful? How would I know?

- What would that success look or feel like for each of the parties with an interest?

3. Brainstorming (Ideas?)

Be complete, open, non-judgmental, and resist critical analysis. View from all sides.

- What are all the things that occur to me about this? What is the current reality?

- What do I know? What do I not know?

- What ought I consider?

- What haven’t I considered? Etc.

4. Organizing (How?)

Identify components (sub-projects), sequences, and/or priorities.

Create outlines, bulleted lists, or organizing charts, as needed for review and control.

- What needs to happen to make the whole thing happen?

5. Next Actions

Determine next actions on current independent components.

- What should be done next, and who will do it

If more planning is required, determine the next action to get that to happen.

Source: ALLEN, David (2015) Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-free Productivity

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------Project Creation Template

----------------------------------

Project/Intention Title:

Purpose/Guiding Principles (Why?):

Mission/Vision/Goal/Successful Outcome (What?):

Brainstorming (Ideas?):

Organizing (Subprojects, major stages) (How?):

Next Actions:

1. …

Support Material

…

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Engaging in the moment

Perfecting the art of using experiences to forge your path involves two challenges. First, you must move beyond the busyness. You must move to a place where you can think with a clear mind and be ready for anything. Then you must let go of the past, get beyond limiting beliefs, and engage in what is immediately before you.

To engage fully in the moment and leverage the experience to help you change and grow, you can ask yourself specific questions at any given choice. Some examples of the specific questions are:

- ‘What does this mean to me?’

- ‘What does this feel like?’

- ‘What does this tell me about me?’

It is through these focused questions that the true nature of the experience becomes evident. That enables you to see the learning opportunity. In this place you have less resistance to replacing the beliefs that served you up until that moment.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Identifying limiting labels

One method for identifying limiting labels (i.e., those that no longer serve you) is to observe how and when you use absolutes like ‘always’ or ‘never’.

As an example, ask yourself, if any of these phrases feature in your conversations:

- ‘I always think BLANK.’

- ‘I always feel BLANK.’

- ‘I always say BLANK.’

- ‘I always do BLANK.’

- ‘I always have BLANK.’

- ‘I always buy BLANK.’

- ‘I always wear BLANK.’

Or you use ‘never' with any of the examples above.

For each of these BLANKs, ask ‘Why?’ (i.e., ‘Why do I always do BLANK?’).

When you get the answer, reflect on the origins. See if you still feel the same now. If the answer includes an ‘always’ or ‘never’, think harder (i.e., ‘I always wear blue, because I always have’, isn’t a reasonable answer). And look out for using someone or something else as the justification, (i.e., ‘I always do it that way, because my father did it that way.’). This is a borrowed belief.

It is likely that, if you can’t provide your own answer to the why question, you are using a label for reasons that aren’t your own. Finding the ‘why’ will help surface if the label is one that you might want to peel off, or the sign is one you want to take down.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Instant Sleep

Mindfulness techniques are helpful in getting to sleep but are not for everyone. And, pushing thoughts away from your conscious mind still involves thinking.

If you are not able to instantly switch off, try this technique for stopping thinking. After laying down and getting comfortable, close your eyes and look at the inside of your eye lids. Acknowledge the colours for a moment, then bring the focus of your eyes together. It is almost like crossing the eyes when making funny faces as a kid, but not to that point of it being painful. Repeating that slowly four or five times is generally enough. You’ll know it is enough because you won’t remember how many times you did it. Instead, you will fall asleep.

This technique is especially useful if you are overtired, preoccupied, or want to take a twenty-minute power nap. With better quality sleep, comes better quality decisions, and that is where the truth to recovery rests.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Kofman’s approach

Fred Kofman, in his 2006 book, Conscious Business: How to Build Value Through Values, provides wonderful insights for breaking free of limiting beliefs.

His approach helps in moving away from the victim mentality, where one perceives themselves as a victim despite no real crime or harm. It applies equally to the closed or fixed mindset, where one is hellbent on staying with a particular direction.

Here is a summary of Kofman’s approach:

Stage 1 - Recognize where you are trapped in a victim or fixed mindset. Pay attention to words that focus on elements that are out of your control (i.e., listen to when you refer to other parties as being the problem). Stay curious and consider the challenge you are facing and how you responded. Try avoiding dwelling in this exploration, just pay attention to when you blame others.

Stage 2 – Disarm the blame. Consider how would the other parties explain this situation. Consider to what extent you are responsible for the situation, even if just a fraction. Ask yourself, ‘How is this working out for me?’. Try to stay focused on the story or the problem and not the relationship with the story. Avoid dwelling too deeply on what happened to you.

Stage 3 – Embrace agency: Consider what you could do differently, how you could be challenged, and what are you willing to try.

In general, avoid jumping to solutions before exploring what you can control.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Lion in chains

Picture a room with a single door. The room represents a life experience. Picture yourself in that room ready to experience what the room has to offer.

Now what if a lion is dropped into the room. What would happen?

It is likely, all things being equal, that eventually the lion would get hungry and want to eat you. In that eventuality, what are your options? Most would choose to leave via the door, immediately. That would likely apply to every other time a lion is dropped into the room you are in.

What if there was a possibility that a lion might be dropped into every room, from that moment on. How would your experience of life pan out?

Dreadful and limited is the most likely answer. You wouldn’t be able to stay or even enter any room. You’d miss every potential life experience.

Now, what if someone comes along and puts a chain on the lion and anchors it to the wall?

Well, you would be able to enter the room again. However, the lion would need to be chained down for every room you may enter.

This is not a good thing. It is a trojan horse.

If that other person is controlling the lion with chains, they are controlling you. They can choose to use chains or not. They can determine which room you can enter and which you cannot. Your potential for life experiences is controlled by them. You allow yourself to be the victim. Not a victim of the lion’s hunger, but of the other person’s will. You are allowing them to depower you. Your safety becomes dependent on somebody else putting chains on every lion.

You may counter that claim with the thought that you could learn to defend yourself against the lion. That might work but has risks. Another possibility might be that you learn to tame the lion. You could learn how to put chains on it yourself, so to speak. That way you could go into any room you like, regardless of whether there is a lion in there or not. You’d be safe without anyone else’s intervention. You’d stay empowered. You would experience life to its fullest. You would have agency.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Managing derailing behaviours

There are three potential strategies for managing derailing behaviours from those you care about or must deal with for professional reasons:

Confronting: This strategy involves telling them straight and giving them direct feedback. However, confronting is only worthwhile if the other party is in a place of seeing growth as a possibility. If they aren’t ready to learn and forgive themselves, the confronting approach won’t help. In certain situations, confronting can even cause more harm and make things more challenging. For example, standing up to a skilled bully can have you looking like the aggressor and have the bully looking like the victim. This doesn’t serve anyone.

Ignoring: This strategy is as the title suggests. Turning away and ignoring those who are behaving badly helps in the short term. However, by ignoring them, you are buying into their misery. That may cause more hurt for you than dealing with the hurt caused by the misery they inflict.

Disarming: In his 2015 book Talking to Crazy: How to Deal with the Irrational and Impossible People in Your Life, Mark Goulston explores various forms of irrational behaviour. As well as helping to understand the irrational behaviour, he provides details on how to manage ourselves in these situations. Goulston also shares ideas on how we can help the other person get to a better place. For example, Goulston’s insights provide a method to counteract negative behaviour. He suggests that you try to be over-the-top with positivity and you do it constantly and deliberately. As often as you can, you start by asking the person how they are. Or in a professional context, you ask, ‘How are things going for you?’ You do it in a positive and cheerful manner. Then when they reply with the usual, ‘I am tired’, ‘I am not well’, ‘I have got loads to do’, or whatever it is, you empathise (i.e., you say, ‘That must be terrible for you’, or something like that). You then change the subject to something positive, and perhaps unrelated to the concern expressed (i.e., when hearing about a poor grade in math, you might say ‘It is great that Johnny got eighty percent in his spelling test’). Another example could be on hearing about ‘being really busy’, you could say, ‘It is great that the company closed that deal with xyz the other day’. Even if the other person doesn’t hear or take in what you are saying, by using this approach you maintain your positive state of mind. You may also feel that you are there for the other person when they are ready to move forward.

When you encounter someone exhibiting derailing behaviour that you cannot just remove from your life, like a family member, colleague, or important work contact, you need to do what you can to help, but not at the risk of compromising yourself. Whether the person is just going through a bad patch or has some clinical issues, while useful at times, confronting or ignoring only makes things worse for you, and them. Disarming, using techniques like deliberate positivity, on the other hand, helps you maintain your own positive state and may even help them with theirs.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Managing emotions

Emotional intelligence can be taught and improved with practice. A good place to start is labelling, also known as naming emotions.

This is the technique of using your self-talk to your advantage, and there isn’t much to it. You simply use a phrase like ‘I am experiencing excitement’ or ‘I am experiencing fear’ or ‘I am experiencing anger.’ Saying it quietly in your head is enough. Saying it out loud can help also, particularly if that emotion is strong. The technique is enhanced by repeating it over and over, until you feel a sense of calm and control returning. Once that sense of calm and control returns, your thinking brain is back in the driver’s seat. Once you are in that place, you can look at the emotion and its meaning. Clearly, none of this works if you can’t observe the emotion in the first place. Practice is the key to that. It is best to start small and build up.

To build the skill, you start with naming emotions in normal situations, like joy, and contentment. You name these in your mind. From there you observe how the mind reacts to thinking about them. While it may feel hard at first, it gets easier with practice. This practice is explored further as part of the coaching corner topic titled ‘Strengthening the attention muscle’.

An effective way to manage strong emotions is to tell yourself that they are with you because you care.

When you are feeling nervous, consider that this is because the challenge at hand is important to you. When you are feeling scared, consider that perhaps you don’t want to let yourself or others down. When you are feeling angry, consider that it might be that your expectations haven’t been met. When you feel love, consider that you are engaged in something of meaning. When you feel excited, consider that you are engaging in something that is important to you.

When an emotion captures your attention, ask yourself, ‘So what?’. Explore what level of importance you are associating with the thoughts that follow that question. Look for the level of ‘care’ you have for those thoughts. It is through this self-talk that emotions get managed.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Managing the ego

While you may consult externally when making decisions, ultimately, it is with yourself that you must agree. Without that internal agreement, you will have no chance of being on the path of your choosing. You will lack agency.

When you are challenged or feeling strongly about a course of action or inaction, you must listen to your self-talk. The thinking that comes from these voices in your head will have two influences. The first is aligned with ego and the other is aligned with your true purpose (i.e., agency).

Ego is steering you when you feel yourself responding in an aggressive or defensive manner to a change in conditions or an unexpected event. The ego-driven self-talk will look for ways to change something about that new condition or unexpected event. If that something is good and is happening directly to others, the ego will look to take the rewards or diminish the value of that good thing. If that something is bad and happening directly to others, the ego will relish that it isn’t happening to you, try to get away from it before that bad thing comes your way or act the hero and intervene before truly understanding the relevance of that something. If the something is good and is happening to you directly, the ego will either feel guilty and undeserving of such a good thing or show off, claiming it for itself, and ensuring everything was because of the ego’s action, when that might not be the case. If the something is bad and it is happening to you directly, the ego seeks to blame someone or something else. The ego will put distance between you and any related action that might have led to that change in conditions or unexpected event. Worse still is that the ego is possibly not aligned with your path. It will likely be aligned with what you perceive others find important.

The alternative is agency. Firstly, and foremost, agency influenced self-talk doesn’t differentiate between ‘happening to me’ or ‘happening to you’. It understands that something is simply happening. Secondly, when having agency, you feel there is opportunity and learning, no matter if the something is good or bad. Alignment with agency ensures the something is integrated into your path. When the something is good, agency will ensure the experience is rich and engaging, and that there is maximum opportunity for growing and maintaining momentum. When the something is bad, agency will look for the meaning in the experience to learn from it, but also to find ways to minimize its impact so it is less painful or upsetting for all involved.

The trick to managing the ego is to listen to your self-talk. Listen for the conditional statements. Listen for thoughts that involve changing someone or something. Equally, listen for self-talk relating to blaming someone or something for things not being a certain way. And finally, be aware when your thinking is trying to justify something based on someone else’s beliefs. Look for it in others too. They may think they are helping you, but it might be their ego talking, not agency.

Here are some examples of the self-talk you may hear when the ego is influencing:

- ‘To achieve this, she should …’

- ‘This would have worked if only he had …’

- ‘She needs to do … before I can do …’

- ‘I can do that better than they can; I should intervene’

- ‘I can’t do that because of …’

- ‘That can’t happen until …’

- ‘I can’t be that until … happens’

- ‘I am so much better than this, if only I …’

- ‘That will never happen without first …’

- ‘This always happens when I …’

- ‘We must do it this way because … says so’

- ‘I can’t do it that way because it says so in …’

When you sense this type of conversation, look for unconditional facts. Engage in those fact-based thoughts and that encourages agency.

Here are some examples:

- ‘It’s cold.’

- ‘It’s hot.’

- ‘I am frustrated.’

- ‘I am fearful.’

- ‘I am tired.’

- ‘I am hungry.’

- ‘The sun is warm.’

- ‘I am excited.’

- ‘I am healthy.’

- ‘I am loved.’

- ‘He is professional.’

- ‘They are a great team.’

- ‘She has the company’s interests at heart.’

- ‘We have an excellent product.’

- ‘We have wonderful children.’

- ‘We want the best for each other.’

- ‘We want the best for our children.’

Allow the thoughts that come from those statements to spread through you and replace any self-talk about changing something or someone. A focus on truths should help you see the actions available to you in the current context. You should see what can be done right now, given the resources at your disposal, your talents, and considering the constraints of your circumstances at that precise moment. Agency will drive you closer to your true aims when the ego isn’t getting in the way.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Mastery in accountability

The content here, in part, addresses one of the five mastery topics that are proposed as a possible approach to freeing the psyche of your daily burdens. This proposed approach helps make sense of it all and helps with full engagement with everything that has importance. The five mastery topics in this approach include presence, awareness, crafting, accountability and focus.

To achieve mastery in accountability you need to be doing the following:

Step 1: Use your lists.

It sounds kind of obvious, but often, when you find yourself frustrated with lack of progress or having a feeling of under-achieving, it is because you have not used your lists of decisions. Instead, you have just gone and done what is on your mind. All the effort put into presence, awareness and crafting is totally in vain if you don’t use the outcomes of those activities. To use the lists, you read them at any point where your next activity isn’t set by a time commitment (i.e., a calendar diary entry). Instead of just doing what you have in your head, which if you are maintaining presence, should be nothing, you must read the lists. The loud ‘do this now’ voice in your head may be guiding you to the most important thing at any moment, but it is also possible that it is not. That thing that is loud in your mind, as per the workings of mind using the theatre metaphor, might be on stage simply because you haven’t externalised it properly. See the coaching corner piece titled “The Theatre Metaphor” for an explanation of the metaphor, which is presented by David Rock in his 2020 book, Your Brain at Work: Strategies for Overcoming Distraction, Regaining Focus, and Working Smarter All Day Long.

The hard truth is that you will never have enough time in your life, no matter where you are in the journey, to do everything you should, could, need, or want to do. The list of things to do will always be longer than the amount of time you have. The key is to have an efficient process to get to the bottom of what is the most important thing to be doing at any given moment, so that you can be certain that your time is being used properly. Once you have this efficient process in use, you will reach choice without burden. This means you will be doing the most important thing to be doing at that moment and hold no guilt or regret about what you are not doing.

Using your lists ensures that you are choosing the most important thing to be doing at any given moment.

Step 2: Be realistic

To achieve the benefits of choosing the right thing to be doing at any given moment: firstly, you need to finish the thinking about things you want to do (i.e., awareness). Then you need to organize the results of that thinking (i.e., crafting). And finally, you need to make time to use this thinking to make decisions about what you will do at any given moment. That decision process involves three parts. Firstly, you need to consider the context you find yourself (i.e., trying to do actions that require an internet connection when you are at 35,000 feet in economy is only going to wreck your head). Secondly, you need to look at how much time you have before the next time-based commitment (i.e., there is no point starting something that takes sixty minutes if you only have thirty before the next meeting). Finally, you need to consider your resources, your energy, and attention (i.e., there is no point starting something that requires good concentration when you have just come out of a mentally draining conversation).

When you consider context, time available and energy, you are better placed to know very quickly which of the things on your lists, is the most important thing to be doing at that moment.

Step 3: Clean as you go.

Completing actions is crucial to achieving your goals; however, losing track of where you are with respect to all associated actions will slow you down. It is important, therefore, that when you finish one action, you close the loop and update your lists with the next action. This housekeeping activity is part of the skill of crafting; however, it is the skill of accountability that will ensure you update the lists and therefore don’t forget.

Periodically, perhaps weekly, you must clean up your list of actions. When you get busy, you might take short cuts. Your list of things to do can become less than effective. There are usually two things that typically cause you to avoid using your lists of decisions. Firstly, you have written down a ‘task’ to save time, when you should take a few moments more to qualify what is the actual next physical thing that will move this forward. These ‘tasks’ don’t get done, because your mind goes into overdrive every time you read them. The second reason your lists need cleaning up is because the level of importance has changed (i.e., while it was important when you wrote the item on the list, it is no longer as important as other things you decided you will do).

Periodically, perhaps weekly, you must look over the list of commitments you have made to yourself, to others, and those which others have made to you. These commitments should be maintained in a list of projects, and delegated lists, as outlined in the coaching corner piece titled “Mastery in crafting”. Reviewing these lists ensures that you have a good sense of the bigger picture. As the week progresses, you might find you have completed an action or two and forgot to add the next action onto your lists. Reviewing the list of aims on your projects list, provides the opportunity to catch things that may be about to fall between the gaps (i.e., to avoid missing a commitment to someone else). This regular review also provides the space to remind yourself of commitments that have been made by others and gives you the opportunity to follow-up again.

You must also do regular housekeeping on your filing (i.e., monthly or quarterly). In supporting the commitments that you make, you will accumulate stuff. This stuff includes physical things, emails, social media updates, news, other forms of instant messaging and, of course, thoughts. All these things are stored somewhere, even if just temporarily while you use them. If you don’t regularly purge these places, they get too full and cumbersome and once that happens, you won’t use them, or you will just pile more stuff on top.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Mastery in crafting

The content here, in part, addresses one of the five mastery topics that are proposed as a possible approach to freeing the psyche of your daily burdens. This proposed approach helps make sense of it all and helps with full engagement with everything that has importance. The five mastery topics in this approach include presence, awareness, crafting, accountability and focus.

To achieve mastery in crafting, you need to be doing the following:

Aspect 1: Maintain a list of aims (i.e., use a Projects list).

An aim, in this context, is something that you are committed to moving towards, in the present moment. David Allen uses the term ‘project’ (See Allen, David. Getting Things Done. The Art of Stress-free Productivity. 2015 ed). Allen suggests that a project is something that has more than one step, where the steps are not self-evident from the outcome and where that outcome is expected to be realized in a year or less. Self-evident means that you understand the steps needed to realize the outcome. Some self-evident examples might be: (1) fill the stapler (assuming you have a well-stocked stationery cupboard); (2) mow the lawn (assuming you have a working mower, and it isn’t raining); and (3) Collect Mum & Dad from the airport. The steps here should be self-evident, so there is no need to maintain a separate project listing. In Allen’s approach, anything longer than a year is really a goal or a focus area.

Aspect 2: Maintain lists of decisions that you have made about what you will do (i.e., use a list of next actions)

A next action is something that you can do now, or anytime from now, and that will move a project closer to achieving the desired outcome. Many confuse the concept of ‘Tasks’ with next actions. They are not the same. For example, you can’t ‘do’ a ‘Weekly Report’, that is a task. You can, however, open last week’s report and prepare it for making changes. This is a specific action that you can do now.

Aspect 3: Maintain accurate records of all date and time commitments, (i.e., use a calendar diary).

It sounds obvious, but it surprising how often people rely on their memories for date and time commitments, especially for personal commitments. As things get complex, with a spouse, and children, it is just unrealistic that you will remember every date and time you have committed to doing something for yourself or others.

Aspect 4: Maintain a later start list.

A later start list is a list of things that you can’t start now, or things for which it doesn’t make sense to start now. For example, ‘renew passport’ is not something that makes sense to start just after you have got a new passport. But it will be something important to do as the current passport approaches its expiry date.

Aspect 5: Maintain a list of things that you are not going to do right now (i.e., use a someday/maybe list).

If you are mastering awareness, it will be easy to know what you will do now and what you won’t. However, you will struggle to let go of it unless you are sure that you will get back to it at some point. David Allen refers to this as a ‘Someday Maybe List’. Another way to think of it is the idea of ‘Deferred Decisions’. Either way, this list is for those things that are important in that they have meaning for you, but not just right now given the other things you know about that need your attention.

Aspect 6: At all times, externalise your repeating thoughts, as well as your worries, overthinking and preoccupations.

Holding onto thoughts of what you need, want or should do reduces your thinking capacity and your ability to focus. In practice, externalising involves physical and electronic ‘inboxes’ to capture your thoughts in the moment. As outlined in aspect seven, below, these inboxes must be cleared to zero (i.e., processed) at the appropriate intervals, and the results of those decisions inserted into your lists as outlined in other aspects of mastery in crafting.

Furthermore, allowing worries, overthinking and preoccupations, excessive access to your thinking space, isn’t productive and does nothing to help you move forward. While chronic stress, excessive worry, overthinking, preoccupation and other related derailing conditions aren’t things to be taken lightly, you have a choice in the short-term. You can choose to manage the moment and engage with what is in your immediate control. This is achieved by using a journal to write down the worries. Journalling makes it easier for you to step back from them, acknowledge where you are and hopefully find what will help you move forward, in the short-term. The journal can be electronic, like a note taking app in your phone or an integrated environment like Microsoft OneNote. Paper works just as well. When choosing the paper journal, be sure to choose a basic journal. Avoid fancy journals that might have you thinking you need to write eloquently. No, for this aspect of externalising your worries, a simple journal is best where you feel you can write anything and in any manner. The coaching corner piece titled ‘Taking stock’ includes some questions that might help when reviewing your written thoughts.

Aspect 7: At predefined intervals, look in all the places you have collected stuff and make decisions about the level of importance.

At regular intervals, perhaps daily, you must review the things you have captured. These items need to be processed. You need to apply mastery in awareness to make choices about the level of importance and then organise the outcomes appropriately. The items to be processed will include physical things, emails, social media updates, news, other forms of instant messaging and of course, thoughts. Also known as unfinished thinking, these new things may be important to you. You need to ensure you spend time deciding what these things mean. You need to consider if you are going to do something with them. Regular and frequent attention to processing is important because if the stacks of new things or unfinished thinking, gets too big, you won’t go near them anymore.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Retrospectives

Best practice in many modern work methodologies makes use of a straightforward review to learn and grow, at the completion of a piece of work.

These reviews occur no matter the outcome (i.e., successful, or otherwise). These reviews typically involve the full team and take a brief period compared to the aspect under review. For example, in the Agile Scrum methodology for developing software, a typical cycle lasts 2–3 weeks. One aspect at the end of the cycle is the retrospective review. It usually takes no more than 30–40 minutes. The key with this, and all forms of retrospectives, is that the learning potential does not get in the way of the momentum. Therefore, the reviews are short, focused, and done in a specific manner. The questions asked at these reviews are positive and focused on learning.

Here are some examples:

- What worked—what can we be proud of?

- What did not work—what will we stop doing?

- What could we try—what unexplored aspect might help?

The process intentionally avoids ‘why’ questions. These types of questions invoke the need to find causes only and defocus the attention on solutions. A well-formed ‘what’ question will inherently involve thinking about the cause but bring focus to the solution. Before answering the ‘What’, our brains automatically join the dots on the causes to understand what did or did not happen. With the correct ‘What’ question, our minds do not dwell on the causes.

A variation of these questions works well for personal retrospectives.

For example, after failing at something, or feeling disappointed or being let down, you might ask yourself:

- ‘What do I have—what can I be proud of or grateful for?’

- ‘What isn’t working— what should I stop doing?’

- ‘What could I try—what steps could I take now or next time that might work better?’

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Scaling Questions

A good method for identifying what you can do about any aspect where you are falling short of what you desire, is the use of the Scaling Question process.

This process helps clarify the current position or relationship to a question, and then induces a positive mindset in bringing focus to the actionable next steps.

Step 1 - Pick an area or topic that you want to look at.

Step 2 - Score it, 1-10

Think about the topic, give it a score between 1 and 10, where 1 is the furthest from where you want to be and 10 is the closest.

Step 3 - Reflect on the score

Considering the score given above, ask yourself ‘What makes this a [n] not a [n ÷ 2]’

For example, if you gave an aspect a score of 4, you would ask yourself, ‘What makes this a 4 not a 2’.

Reflect on this question for a moment or two. Allow the mind to answer the question.

Write down what your mind comes up with, perhaps start a bullet-point list. Ask the question again after writing your first answer. Then ask it again and try to get a third reason. It is ideal to get two to three reasons. Avoid allowing your mind to take the next step just yet. You don’t need to think about what would make it higher or why it is at this score. Just focus on the question.

Step 4 - Look forward at options

Next, ask yourself ‘What would it take to bring this score to a [n+2]’.

For example, if you gave a score of 4, you would ask yourself, ‘What would it take to bring this score to a 6?’.

Once more, allow your mind to reflect on the question for a moment or two.

Try to find specific actions that you can take right now. Ask the question once or twice more to give yourself more possible options.

Step 5 - Take action

Finally, ask yourself ‘What will I commit to doing?’

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Searching for limiting behaviours

Limiting beliefs—those that no longer serve you—and their associated behaviours can let you down.

When searching for behaviours that need changing, ask yourself:

- Does this serve me?

- Does this serve others?

- Does this feel right?

Ask those questions when you are unsure about a choice you are making. Ask them of your routines and habits as well as the commitments you have made to yourself, to others, and your communities. Ask these questions when you are in the middle of an engaging experience. Take care to check that what comes back isn’t based on high resistance, like fear, or avoidance. Do this by asking yourself if what you are thinking about, involves changing someone else’s behaviour or projecting one of your own beliefs on them. Ego is therefore the driver. When you get an answer like this, ask again. And, once more, listen. With time, this process will bring you to a conclusion that feels right and good. Focus your time and energy there.

When really stuck, ask yourself, ‘What could I do now that would serve me and others?’. Then listen again and apply the same process of checking for high resistance.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

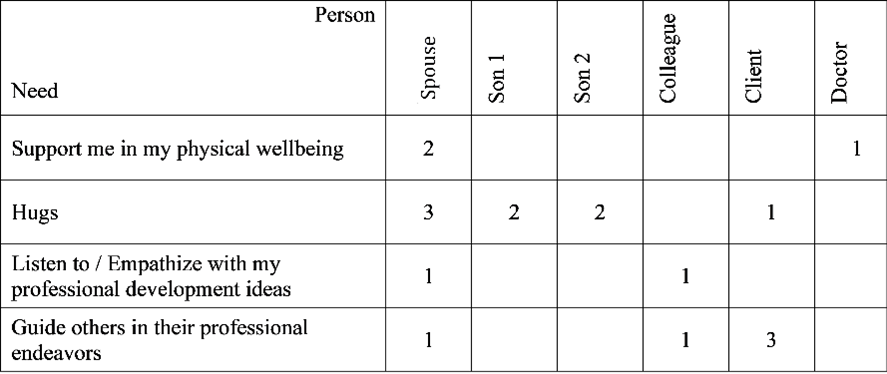

Social Needs Relationship Matrix

The Social Needs Relationship Matrix is used to assess whether your social needs are being met by those in your world.

This tool helps you see where you need to focus effort, both from an initial investment, and, from a maintenance viewpoint. It gives a clear line of sight.

The steps are as follows:

1. Open a spreadsheet or use a piece of graph paper.

2. In the first column, down the page, list your social needs, putting one need per row.

In exploring your social needs, look at what you need in terms of giving and receiving. Also look at aspects of your personal and professional experience. If you get stuck, think about the interactions you have had with others. Consider what topics were part of those interactions. Consider who was doing the talking and who was doing the listening. Look for experiences with others where you felt high levels of emotions, both positive and negative. Describe the opportunities for giving and receiving separately. be very specific when you know there is an interaction that you need from one individual and be more general when a group of people are involved.

Here are some examples:

- Support me in my physical wellbeing

- Support others in their physical wellbeing

- Support me in building better habits

- Support others in building better habits

- Listen to/empathise with my ideas of intimacy

- Guide me in my ideas of intimacy

- Listen to/empathise with my ideas on building friendship

- Guide me in my ideas of building friendships

- Listen to/empathise with my personal development ideas

- Guide me in my personal development

- Listen to/empathise with my professional development ideas

- Guide me in my professional development

- Listen to/empathise with my spirituality related notions

- Guide me in my spirituality

- Listen to/empathise with other’s ideas of intimacy

- Guide others in their ideas of intimacy

- Listen to/empathise with others in their personal endeavours

- Guide others in their personal endeavours

- Listen to/empathise with others in their professional endeavours

- Guide others in their professional endeavours

- Sexual Intimacy

- Hugs

- Play

- Physical proximity

- Call me out for putting myself down.

- Call me out for being unrealistic/aiming too high.

- Care for/provide for

- Share joy/humour—family

- Share joy/humour—adult

- Share value creation

- Share growing (pain/anguish)

- Share excitement/wonder

- Share worthiness

3. In each of the column headings, write the name of key people or groups of people in your life. For example, write the name of your girlfriend/boyfriend/spouse in column two, the names of each of your children in the next columns, the names of your parents and siblings in the next set of columns, key extended family members after that, and then your business partners, followed by the names of your close friends. Then put key clients, key influencers and your various groups, communities, and professional associations in separate column headings after that. And, finally, list your support network (i.e., your doctor, coach, trainer etc).

4. Now review each cell and give it a number, if appropriate. Either leave it blank, or give it a one, two, or three. Leave the cell blank if that person or group of people has no impact whatsoever on the social need. Give the cell a one or a two if the person or group occasionally helps meet that social need. Give one if there is a good bit of effort required on your part (i.e., if you must go out of your way to bring this person into your life to help with the related social need), otherwise give a two. Give a three when that person regularly helps you with that social need.

The results would look something like the following:

5. With the scores in place, add them up, and look for patterns. Consider that there is a need for investment when, across your existing connections, you are not getting at least three in total (i.e., in the example above ‘Listen to/empathise with my professional development ideas’ isn’t being met). Perhaps you need to take action to address that. Secondly, look for big winners (i.e., ‘Spouse’ in this example has the highest score). If you are to maintain the current level of wellbeing, you had better invest effort to make sure that relationship is well-maintained.

To work on the patterns, perhaps print or copy the work. Then write your action plan directly against the needs and individuals you want to focus on. Later, you can revisit that piece of paper to reflect on your progress.

The patterns you see in this chart will be relevant for where you are now. Over time, these will shift as you change, and as people come into and out of your life. Perhaps revisit this matrix as you need to (i.e., when you meet new people, lose contact, or something major shifts in an existing relationship).

The matrix provides useful information in helping you manage your network of friends, family, and peers. It will show you where you need to invest and maintain. It will also show you where you have risks. It is worth considering action if you see a single individual scoring two or three times higher than anyone else. Not only does it show that the individual has a lot to shoulder, but it shows you to be in a vulnerable position should that individual no longer be part of your life. That could be because of a breakup or falling out. It could simply be because you change your context, and they aren’t as available anymore. It could also be because of something more painful, like death, or someone becoming mentally incapacitated. The pain and ability to bounce forward after a significant loss is going to be considerably more difficult if that departed individual was also a key part of your support network. There is a lot of merit in widening your network through rekindling old friendships and repairing bridges, especially as you get older. Clearly, it isn’t realistic to suggest that you shouldn’t have anyone in your life that you rely on and will miss dearly. You should just be mindful of how much you focus on one individual and have some alternatives available. It is simply important to have the support around you when you need it.

This piece was adapted from No BS! The Art of Agency. A book by Brad Allen. Each piece is designed to stand alone, offering insights and strategies you can apply directly to your life. However, for a deeper understanding and fuller context, you are encouraged to explore the book in its entirety.

Use and Sharing: Feel free to apply these insights in your personal and professional life for your own growth and development. Please respect the intellectual property rights by not reproducing or distributing this content for commercial purposes without explicit permission. For any collaborative or commercial use, contact Brad.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is intended for educational and inspirational purposes only. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information, it should not be considered as professional advice tailored to individual circumstances.

Strengthening the attention muscle

An essential aspect of your ability to focus is what can be metaphorically called your 'attention muscle'. This concept simplifies the complex functions of brain areas like the Prefrontal Cortex, Parietal Cortex, Thalamic Reticular Nucleus, and Inferior Frontal Junction, which are involved in managing attention.

The 'attention muscle' metaphor helps us understand how to observe our emotions and thoughts more effectively. It is like having an 'inner voice' that guides you in using your cognitive resources wisely. A well-developed attention muscle enables you to remain calm and connected even in the face of adversity. This means you can:

- Regulate your emotions and thoughts.

- Engage appropriately with complex situations without reacting impulsively, such as lashing out or withdrawing when faced with challenges or opposition.

In essence, strengthening your 'attention muscle' helps you respond to life’s trials with thoughtful action rather than knee-jerk reactions.